Written by Petar

Wanted to be an astronaut, ended up exploring comics instead.

Written by Matheus

Filmmaker by day, Wishlistmaker by night. Kamala Khan’s unofficial PR team since 2014.

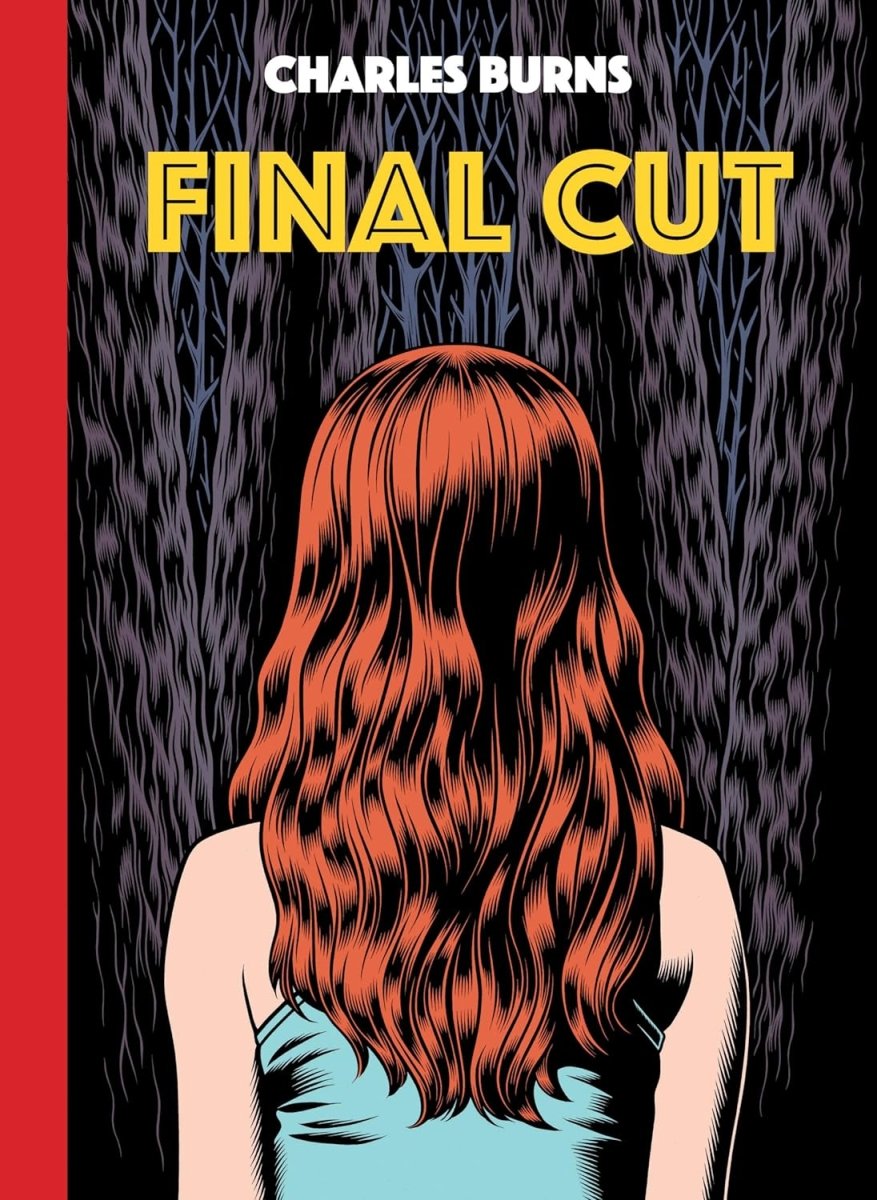

Final Cut by Charles Burns (Pantheon) – by Matheus

This is where I start to think that every choice I made - every nominee I decided to cover when I was splitting categories with Petar - was secretly a masterplan from the universe to make me question the artforms I love. Because here we go again… another book, another deep dive into filmmaking.

If you’re one of those people who were always kind of fascinated by strange sci‑fi‑horror imagery, the kind who stayed up late watching weird old horror films on TV, then Final Cut is absolutely your book.

We follow two perspectives.

Brian is a kid whose real world is already scarier than anything he could draw. But he still draws. Disturbing, haunted pictures - and he still loves those movies. He and his friend Jimmy used to mess around filming their own little backyard versions, but Brian never really grows out of that world. It stays with him, clings to him.

Then there’s Laurie, Jimmy’s friend, who tries to befriend Brian and ends up, almost by accident, becoming his muse. Or, to put it simply, his next homemade movie star. We follow these teenagers as they try to shoot their next masterpiece, unaware of how much of themselves they’re pouring into the lens.

There’s sadness and horror in misunderstandings, in how we misread each other. And the scariest thing here is also the thing movies can’t exist without: projection. That act of placing people into roles in our own fantasies, whether they asked to be there or not.

The horror is in how familiar unrequited love feels to all of us and how maybe we don’t all escape into horror movies, but we all escape into something. We all build private cinemas in our heads, and we cast people we know into roles we need them to play.

And what makes this love‑nightmare beautiful is how human it is, the core of every good sci‑fi story. Even the weirdest creature loves, and hurts, and carries its own past. These characters are all in the middle of discovering themselves, some through agreeing to be portrayed, and others through refusing to look past the portraits they’ve built.

Lunar New Year Love Story by Gene Luen Yang and LeUyen Pham (First Second/Macmillan) – by Matheus

Gene Luen Yang is a favorite of mine. Between American Born Chinese and Dragon Hoops, he’s one of the best around at translating deeply cultural and personal narratives to a wide variety of readers, especially young adult audiences. And if you think that’s an easy audience to reach, you’re out of your mind. To hit them with nuance? Get out of town.

This new book is, on paper, a simple Valentine’s Day story. We follow Val, a kid raised by a single dad, who once bought into every bit of fluff this holiday sells, so much so that he created an imaginary Saint Valentine friend to talk to. But now Val’s older, and he’s ready to give up on the whole thing.

The beauty of the book is in that shift, the things we love and believe as kids - the certainty that you deserve a love story - and how fast those beliefs can vanish once reality comes crashing in. Suddenly, not everything is as crystal‑clear and beautiful as you thought it would be.

And yeah, this is very much a YA book. I’m not here to convince you it’s anything else. If that’s not your thing, this might not win you over. But here’s the thing, Gene Luen Yang is a clever little fella and a damn good comedy writer. Even if you roll your eyes at the genre conventions, he’s going to make you laugh every other page, almost like he’s saying, “Don’t worry, I’ve got you.” (Not that he really needs to.)

Sure, you can see the ending coming from a mile away, but in that good way, like watching a movie you’ve seen a hundred times and still love. This is absolutely that one Netflix teen‑romance movie you adore but keep under wraps, the one you don’t admit to rewatching.

What makes it stand out above the average is how specific it is, rooted deeply in Asian‑American culture, in ways that enrich the characters and give a tired genre new rhythms and new dynamics to play with. No one does that better than Gene Luen Yang, a writer confident in his voice, deeply in love with the culture he grew up in, and more than capable of making the rest of us fall in love with it too.

And you know, you do deserve that love story. It just might not be the one you thought.

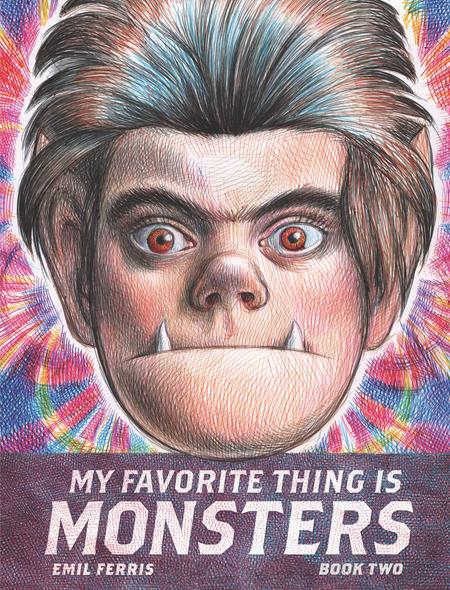

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Book Two by Emil Ferris (Fantagraphics) – by Petar

After seven years of waiting, we got the second part (and the conclusion) of the story of Karen Reyes, a 10-year-old trying to solve the murder of her upstairs neighbor Anka Silverberg. The results? Very inconclusive.

If you read the first book, and you are wondering how Emil Ferris is going to solve all the dangling plot threads, or bring everything together, you might be disappointed. Instead, she lets the story run amok, to the point that it feels a bit untethered and all over the place. Furthermore, she uses a lot of allegories which are not that subtle, and could be read more as tired tropes. With lots of over-the-top pulp added for good measure, we have a messy story that doesn’t even resolve everything at the end. With all the controversies surrounding the book (there was a legal dispute between Ferris and Fatagraphics that was eventually settled), the result we get isn’t surprising, but could be disappointing after Book One sold so well and was highly praised.

The issue that I had with it is the art. The book is presented as Karen’s diary, and thus done on notepad paper with pencil sketches. While it is definitely a stylistic choice that appeals to a lot of people, it did not to me. I found it distracting and difficult to get into the book, but I will say that it is a personal thing and you should definitely check it out for yourself. One thing is certain – the style of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Book Two is very unique and evocative.

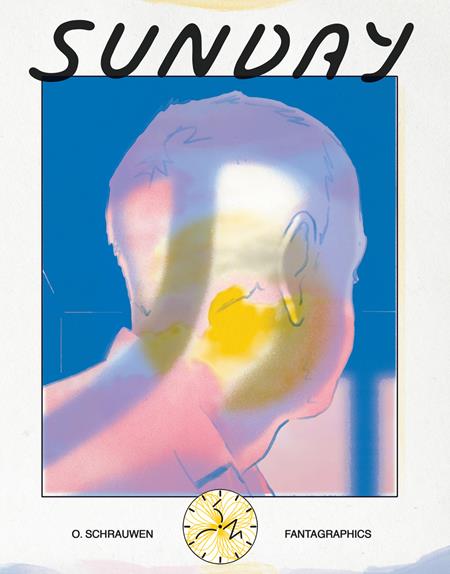

Sunday by Olivier Schrauwen (Fantagraphics) – by Matheus

You know a book is going to challenge you when it begins with an instruction.

It’s simple, really. (Wink, wink.)

In Sunday, we’re following an ordinary dude on an ordinary Sunday. The text boxes above are his thoughts. The images below tho, they’re not necessarily representations of those thoughts or memories. The author describes them as a free‑floating camera with the free will to drift wherever it wants. At one point, he even suggests you stop reading and go grab a coffee (something I also recommend.)

The pacing of the book is wildly experimental. It can be a lot, it can be nothing, and sometimes it’s a strange, mesmerizing mix of both. It says so much in one panel and absolutely nothing in the next and that’s exactly the point. Much like your own day, it’s funny, it’s boring, it bursts with meaning and then suddenly feels empty. That’s the beauty of it.

It’s shockingly easy to identify with the bullshit running through the main character’s head - the utterly stupid little thoughts that pop up uninvited - and the courage it takes for the subject to expose himself like that is remarkable because it is indeed a real family member of the author we’re following. Together they tried to reconstruct this single, ordinary day, and it’s so raw and so real that it becomes hugely relatable. It turns out we all think the same silly things, do the same small rituals, catch ourselves spinning in the same loops. Through that honesty, the book quietly builds a character out of the moments that aren’t ordinary. Because it’s in those flashes, those thoughts that escape common ground, that we see someone’s true shape. It’s a hell of a character study hidden in plain sight.

It’s very much an experience. I kept thinking of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood, born from that same spirit of narrative experimentation. If you’re interested in seeing where comics can go, what kinds of storytelling they alone can pull off, this book is essential.

I had my ups and downs with it, sure, but I have to say that last page made me gasp. After spending a whole day in this guy’s head, the sudden absence hits like a punch. It sunk in, and it blew my mind a little.

Truly brilliant.

Victory Parade by Leela Corman (Pantheon) – by Petar

Rose Arensberg is a welder in the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War II, waiting for her husband Sam to return from Europe. However, there is a problem – Rose has fallen in love with a disabled veteran. And this is just one of many conflicts you will find within the pages of this book.

Leela Corman tracks the day-to-day challenges in the lives of Rosie the Riverets, women who were manning the factories and shipyards during this tumultuous time in American history. Other than Rose, we follow the stories of Eleanor – her young daughter – and Ruth – a Jewish refugee under Rose’s care. This is the story about wartime and about mass trauma as well as the personal battles we all face.

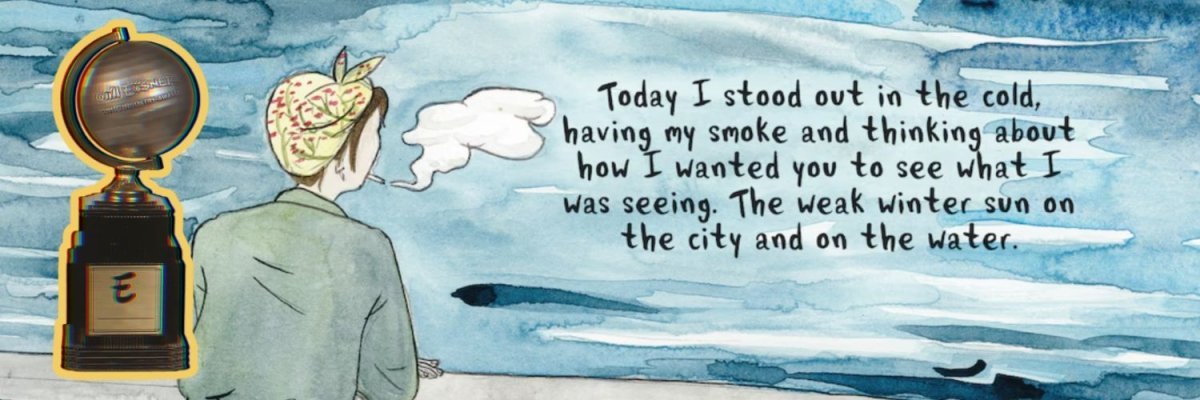

Corman’s art is often static yet always expressive. She uses water colors to paint the horrors as well as the ordinary to interesting results. Victory Parade is very expressionist in its storytelling – you will either hate it or love it, but it will not leave you emotionless.