Written by Petar

Wanted to be an astronaut, ended up exploring comics instead.

Written by Matheus

Filmmaker by day, Wishlistmaker by night. Kamala Khan’s unofficial PR team since 2014.

Alan Scott: The Green Lantern, by Tim Sheridan and Cian Tormey (DC) – by Matheus

Queer superhero books are plagued by demands. They need to be representative, but they also need to be the right kind of representative. They need to be a positive representation, but not so positive that they stop feeling real. They need to be about love, but also about positive love. And through it all, they still need to be superhero comics so you’ve got to have drama, you’ve got to be funny, you’ve got to hit those big action beats. You need to be romantic, but not too much, because God forbid the romance overshadow the plot. You need to speak directly to queer readers, but also be broad enough not to alienate the market at large.

Ah, and on top of that? You need to justify yourself at all times. You need to make the case, sometimes outright argue, for the very existence of queer books in the first place.

They want our stories to prove themselves at every stoplight, every page turn. And if one book falters, if one character “doesn’t sell”, who knows how long it’ll be before another queer hero gets their shot again. It’s exhausting and suffocating. It’s hard to find room to breathe.

And yet, Tim Sheridan and company make the most out of the sliver of space they’ve been given in Alan Scott: The Green Lantern. Alan Scott and the JSA carry legacy, and legacy can be a tricky thing when you’ve never been allowed the full scope of yourself in the first place. What I think this book does so well is wrestle with that truth. That one of the most violent things you can do to a person is to deny them the chance to see things through. To cut off their story mid‑sentence and tell them that’s all they get.

When superhero comics like JSA or Captain America loop back to WWII, we’re usually shown two clashing images at once. On one hand, the building of an almost childlike nostalgia for “simpler times,” pre‑war ideals. And on the other, the brutal tearing away of that illusion, the sudden, shattering realization that those ideals were never real, that the picture itself was fake, and how devastating that ripping‑apart must have been for those young men. In comics, though, these men survive. They step out of that past into our present, carrying the pieces of those broken images with them, trying to make sense of what’s left. It’s a simple but potent metaphor. A set of images at war with themselves.

Putting a queer perspective into those characters isn’t entirely new, but it adds something sharp. Because once you realize the image is a lie, that realization hits a thousand times harder when you know that parts of those pictures were always taken in the shadows. Cut out, erased, deliberately unseen. That queer layer breaks the easy nostalgia clean in half. It refuses the comfort of a simple golden past and shows how much was stolen, how much was hidden, how much is still left to uncover.

But to continue the mid-sentence interruption and maybe dare a little bit for both the image and the realization after it not to be so squeaky-clean after all, then we have a Eisner-nominated book. And with every complexity they are allowed, they make the most out of it. I just wish it didn't need to revert back to the action beats? For sure. But we take what we can get, I guess.

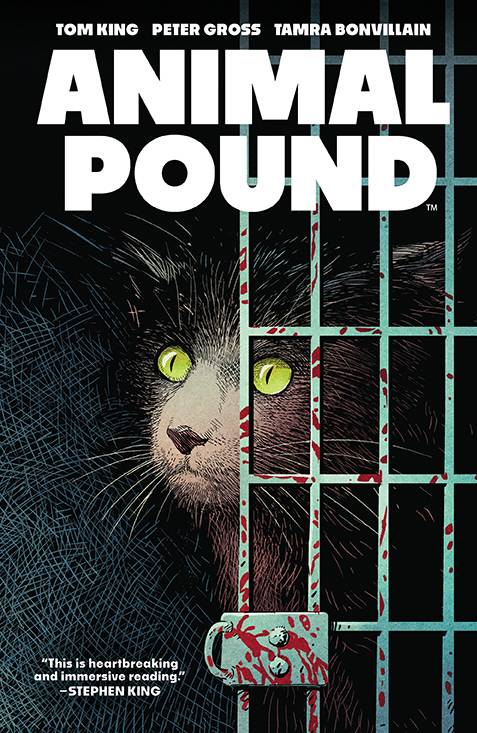

Animal Pound by Tom King and Peter Gross (BOOM! Studios) – by Petar

Every now and again, there appears a work that tries to emulate a work of classic literature, or “modernize” it and adapt it for modern times. Animal Pound doesn’t hide this – it wears it openly on its sleeve. King himself calls it an update of Orwell’s masterpiece. However, I would say that the results we get are mixed, and I would definitely not go as far as to call it an upgrade. Instead, it lives in the shadow of a far superior work it tries to mirror, with some fun ideas and a messy execution.

I want to be very clear here – I don’t have a problem with the message that the work is sending – especially with the horrific things happening in western politics today. However, my main problem is that this is not a message that is revolutionary or particularly brave. Instead, it’s a retread of something that we know to be a burning issue, dressed in a coat that doesn’t fit it. I think this is the main problem I have with the work: Orwell was a democratic socialist and offered a critique and analysis of the very movement he belonged to and how extremists can turn it into something horrific. King doesn’t really offer any in-depth analysis and commentary, even though he wishes the book to inspire essays and conversations. Instead, he gives a clear-cut “bad vs. good” story and then does nothing with it.

So, what is the story of the book? Well, it follows an animal pound, where a dog Lucky has his last conversation with a kitty Fifi. Lucky is old and has seen a lot, and before he goes to bigger pastures, he passes on his final message to Fifi – one day, dogs and cats and rabbits will all live together, and it’s the doors which humans can operate that keep the animals contained, separate and controlled. Years pass, and Fifi is now an adult cat, plotting with a dog Titan to overthrow humans. Of course, once they do, they promise for all the doors in the pound to remain open, but troubles ensue…

There are many characters in the book, named and unnamed, but only a few that really matter or stay memorable. Fifi and Titan are the main protagonists, if you could call them this, and Piggy, a slobbering, cowardly bulldog is the antagonist. I really enjoyed some of the ideas King presented in the book – the animals establish a voting system which needs to be adjusted due to different numbers of animal species – one animal is not worth just one vote since rabbits would easily overtake everything – but instead, they establish the weight as the voting power – thus we get a fun, double-meaning of the title animal pound.

However, I really do wish King developed some more ideas. He never really extrapolates or explains the system these animals live in – how are the humans letting this pound run freely for so long? If the animals have learned to write (as is explicitly stated), why have they not communicated their needs with the people instead of rebelling in blood and violence? And of course, one of the biggest critiques King gives is that animals of all kinds – dogs, cats and rabbits – follow a leader who explicitly does not wish them well – yet King does not really dive deeper into the issues of why – and that’s my biggest gripe with the book. If you want to criticize something so it sparks discussions, I believe you should at least offer some examinations of the topics you’re addressing. Otherwise, a pamphlet with a list of question could do the job just as easily.

That pamphlet, though, would not look as good – and that’s probably my favorite part of this book. Peter Gross’s art is engaging and evocative. Animals show clear emotions and the main players are easily recognizable – for dogs this comes more easily due to diverse breeds, but even cats get the same treatment. This is, of course, supported by Tamra Bonvillain on the colors. Together, they work to give a very realistic and engrossing artwork, full of little details that you might miss if only rushing through King’s endless narration boxes. The book is definitely nice to look at, even though sadly you might have a feeling of “already seen it” while reading it. But please do let me know if your opinions on it differ. Tom King wanted us to discuss it, after all!

The Deviant by James Tynion IV and Joshua Hixson (Image) – by Petar

I was genuinely surprised when I saw this book was nominated for this year’s Eisner’s awards. Not because I don’t think it’s good (I do – but I tend to like most of the stuff Tynion writes, after all), but because the release schedule has been so drawn out and dispersed that I would often find myself forgetting the book even exists, and would then need to go back and reread it for myself. Checking back at the calendar, I see that the eight issue came out in October 2024, with the final ninth issue coming out in March 2025, and I think that paints the picture well.

That said, going back and reading the book as a whole, I do think it is a very enjoyable experience. The story takes place in modern day (as of the publication of the first issue: 2023) Chicago, and follows Mitchel, a deeply-troubled and aimless comic book writer, as he sets out to write a story about the “Deviant Killer” – a man accused of gruesome murder of young men fifty years earlier, who still claims innocence after all those years. Recognition starts developing a bond between the two men, who are unaware that at the same time, another killer dressed as Santa Claus is about to commit a series of murders eerily similar to the first ones.

The story is your classic whodunit mystery, with an angsty protagonist, an unusual detective and a ridiculously dressed yet appropriately creepy killer. It reminds me of Silence of the Lambs, and it feels like it was created to deconstruct and address that story in particular. Silence is known for angering many an LGBT journalist due to its murky portrayal of Buffalo Bill – a distressed individual whose goal is to wear women’s skins. There are themes of trans identity and gender that are explored in both the book and the movie, but the outcome is pretty messy. Tynion takes this and flips it to its head – the “original” Deviant Killer is unabashedly gay, and it was this “otherness” that caused him to be the main suspect in 1973 Milwaukee. Tynion explores how identities are formed in more conservative environments like small towns, and how they can influence people’s perception of what a person is capable of doing (that being – it’s easy to move from “gay” to “serial killer” and sentenced for life even if innocent).

Joshua Hixson tackled the art on the book (colors included), and does a spectacular job with it. Since we don’t really get internal monologues of characters, he uses dramatic angles and shadows to cast doubt even for the most mundane settings like Christmas shopping. Meanwhile, he paints murder scenes in visceral details, pulling back on color when the killer is stalking his victims to build anticipation and dread. I don’t think a book has ever felt more like a slasher movie to me than this one, and going back to it now that it’s done was a treat. Now all I need to do is wait for that oversized hardcover edition…

Helen of Wyndhorn by Tom King and Bilquis Evely (Dark Horse) – by Matheus

This is an A‑Team level book.

If you haven’t checked out their previous collaboration, Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow, go fix that right now. That book was a punk‑rock re‑edition of Kara Danvers. It was both the best‑written and best‑drawn book DC has pulled off in years (honestly, maybe this whole decade). It’s the foundation of the Supergirl movie coming next year, and if you loved those final five minutes of Superman like I did, you owe it to yourself to go straight to the source.

So when this new creator‑owned collaboration was announced, with the exact same people, it instantly shot to the top of everyone's pull list.

Let me geek out first before we even touch the plot: this book features fellow Brazilians and absolute megastars Bilquis Evely and Matheus Lopes, and their talent is beyond comparison. The panels aren’t just rich with detail. They’re infinite in their inventiveness, layered with a sense of wonder that feels like no one else could have dreamed it. To watch them breathe life into impossible worlds is a privilege. Truly. Their art leaps off the page in ways that make you feel like you’re falling into another universe entirely.

To every kid who once woke up in the middle of the night and checked the back of the closet, just in case it opened into Narnia, this duo is what you were imagining, only ten times better. Honestly, I’m not convinced they don’t have access to Narnia. And since they live in the same city I lived in until just last year, maybe kid‑me wasn’t wrong after all. Maybe Narnia really is somewhere in Brazil.

The book itself begins with Helen, a rebel kid, the daughter of a so‑called cheap‑fantasy novelist who, in the aftermath of his suicide, is sent to live with her grandfather. We see Helen through the eyes of a governess hired to keep her “on the straight path.” But then the book peels back its layers, and maybe those fantastical stories her father wrote weren’t cheap at all. Maybe they were real, glowing with richness. And quite a lot of danger.

Kings make this choice of perspective, and that choice is everything. This is a book about how stories are told in the first place. How we inherit them, how we live inside them. We grow up hearing stories from our parents and we carry them with us. Sometimes as roadmaps, sometimes as horror-tales of things we dare not to be. And then, somehow, we find ourselves in the same places they once stood, staring down the same choices, and all those maps blur together.

That’s the heart of Helen Of Wyndhorn. How stories are passed down, how they change hands and change meaning, how they shape us even when we don’t notice. It’s wrapped in a beautiful love letter to the cheap vessels of imagination, that being dollar‑bin comics, one-buck airport paperbacks, the things we dismiss until we realize they’re carrying something precious.

And god-damn if the art is not beautiful.

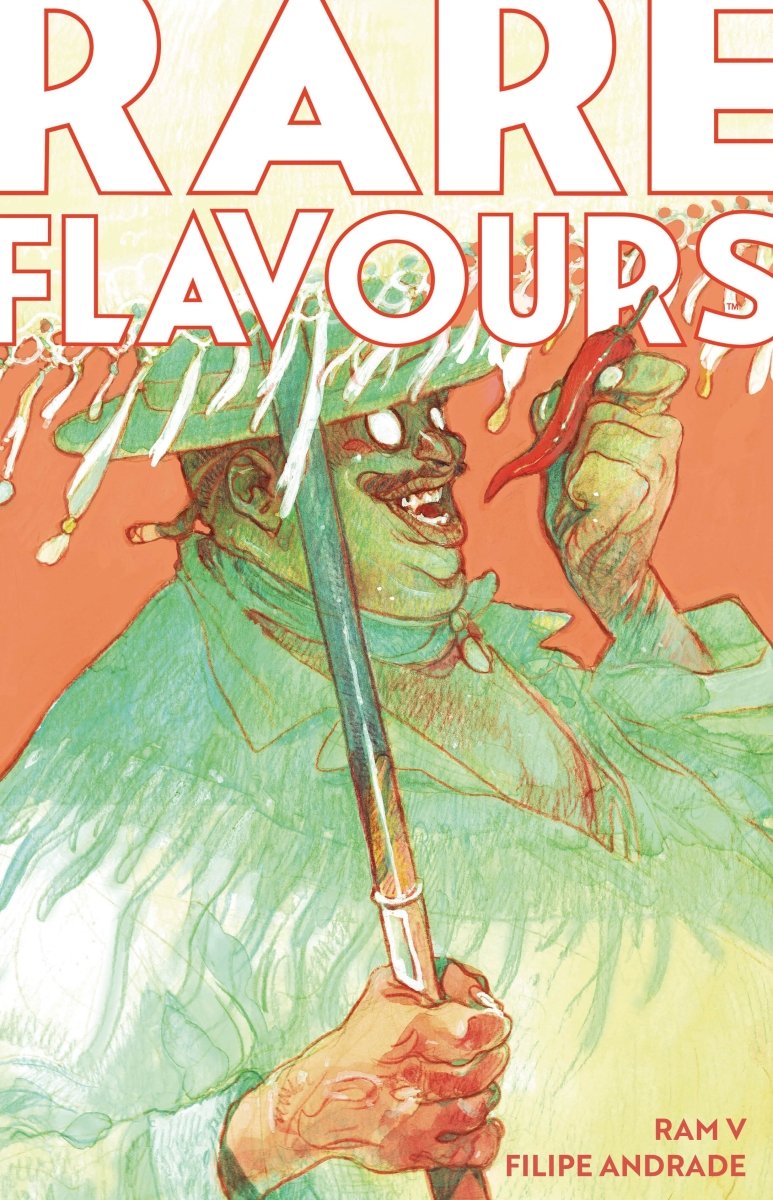

Rare Flavours by Ram V and Filipe Andrade (BOOM! Studios) – by Matheus

Everything sounds so ethereal in those cooking‑travel shows. Every spice is treated like a blessing from the gods, every dish its own religion, venerating its sacred origins. But then, everything also sounds so commercial in those same shows. You too can join the pilgrimage if you buy your tickets right now. Culture is all around us, yes, but culture also comes with a price tag most of the time. The camera becomes a window into someone’s soul… but also a kind of soul‑sucker, extracting what it needs to sell you a feeling.

Why am I tripping this hard in a review?

Well, Ram V kinda took me on a journey with this one.

We follow this figure I can only describe as what if Anthony Bourdain were a demon, hiring a seemingly random wannabe filmmaker - someone who feels like the only art they’ve ever truly mastered is the art of being a disappointment - to document his culinary voyage around the world. But the food is not the only thing he consumes. He also devours the people who make the food.

It’s a very clear metaphor, the consuming of the beauty of art and culture through food. (There’s probably a more elegant way to say that, but the rawness feels right.) The act of taking in someone’s creation, their history, their craft, and making it yours, sometimes violently, sometimes thoughtlessly.

“Oh, that’s why you’re tripping. This motherfucker got you, didn’t he?”

You’re thinking it, and you’re right.

Because art, much like culinary craft, and the pursuit of both, can feel like a window into paradise, but also like hell, burning through every fiber of who you are. I don’t even know if this is exactly what Ram V is going for here, but it’s what I got from it.

And that’s the thing - this is very much a book about what you get from the things you consume - (consume… what a haunted, modern word to use in relation to art) and what those things give back to you. Whether what you take matches what you’ve stolen in return. Whether the act of tasting beauty leaves you nourished… or hollowed out.

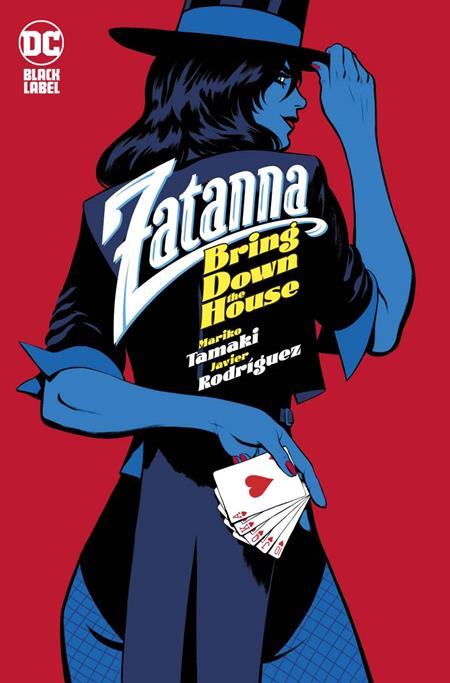

Zatanna: Bring Down the House by Mariko Tamaki and Javier Rodriguez (DC) – by Petar

I just got back from a vacation, having brought Zatanna: Bring Down the House (along with Animal Pound) with me to read while prepping for this article. Over breakfast, my friend would always sneak a peak into what I was reading at the time. While they did enjoy the art of Animal Pound just like I did, they were really blown away by Zatanna: Bring Down the House and grabbed the book to page through it themselves. And there is a reason for this, because the book is absolutely stunning to look at.

Javier Rodríguez serves as the sole artist on this revisionist origin story, and does amazing work (as he always does). Rodríguez works best when he is telling an unconventional story, where he is given free reign to play with the panels, the colors and the visuals. And just like in his work on Defenders or more recent Absolute Martian Manhunter, here he is able to go nuts too – after all, it is a story of mystery and magic! From the very first scene, he grabs the readers attention (even passersby, like in the case of my friend) and doesn’t let it go. The colors are bold, the figurework exaggerated, and the paneling is often a suggestion. It’s magical (if you pardon the pun) to look at!

And then, there’s the story (seems like I have a gripe with a lot of story-writing choices made in these books, doesn’t it?). While I don’t think it is severely lacking, I do believe that it is very much a by-the-book story, and that it is Rodríguez art that really carries this book. So what is it about? Bring Down the House is a Black Label origin story. Having this imprint means that Mariko Tamaki can take any direction she wants, yet she just goes through the motions.

We find Zatanna working shows in Vegas, refusing to use even the word “magic,” while haunted by childhood memories of a forgotten trauma and her father’s disappearance. Due to this being Black Label, Tamaki plays with the characters origins, casting her dad Zatara in a less-than-heroic role he’s traditionally found in (which will probably bother some DC purists), and tries to establish bits and pieces of the magical world and rules. I just wish she went further with the concepts or paced the story a bit better, instead of solving everything in the (spectacularly-looking) final issue. That said, I really did enjoy how Tamaki wrote the relationship between Zatanna and Constantine (who, of course, appears in the story) and would love to see her tackle a project with the duo again.