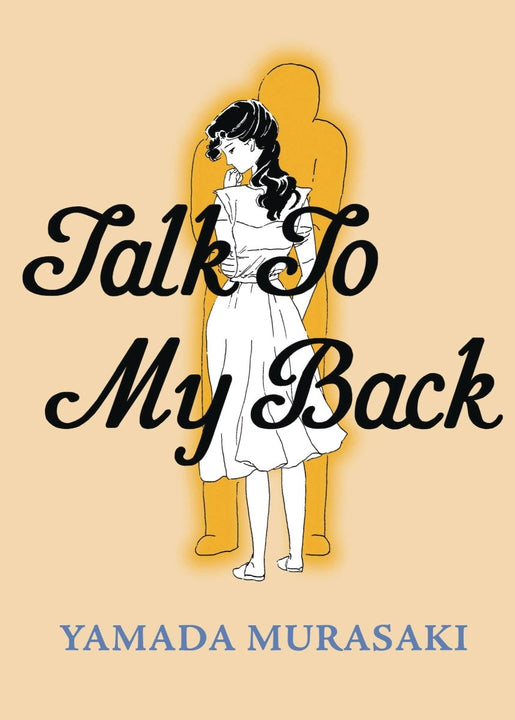

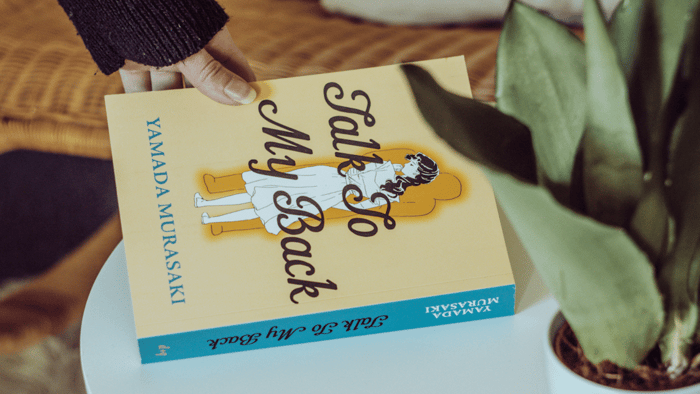

Yamada Murasaki is a mangaka who has received little to no attention in the international market so far. This is changing now thanks to the comic publisher "Drawn & Quarterly," which specializes in alternative manga and older works in the manga sector. In July 2022, they published the manga “Talk to My Back.” In June 2024, another of her works, “Second Hand Love,” followed.

How was it?

In Japan, “Talk to My Back” was published starting in 1981 in the well-known Garo magazine. Later, the work was published several times as a collected volume. What’s it like? Must a woman necessarily be defined and put into a box by the roles she plays in society? Or can she finally hope to be a free person? Reading Yamada Murasaki’s “Talk to My Back,” it becomes clear that this freedom was hard to find in Japan in the 1980s. The protagonist of the manga, Chiharu, nonetheless tries with all her might to free herself from the simple labeling as a wife and mother.

The volume is divided into short chapters, each focusing on a specific episode. Everyday moments, small daily struggles, a young woman trying not to become invisible, almost as if she were part of the house in which she lives, to which she is bound like a curse.

A recurring theme in Chiharu’s life is loneliness: the first chapter of the volume is aptly titled “Lonely Cinderella.” The protagonist’s husband has no problem coming home late from work or even staying out overnight. The moments when his wife puts their two little daughters to bed are the moments when she doesn’t know what to do anymore, and melancholy and loneliness completely envelop her. “The TV is on, but I don’t watch it . . . I have a book open, but I don’t read it . . . Eventually, I come to and realize that I’m hardly here.” Then the clock strikes, and the spell is broken. Time for the dishes. At the end of the chapter, Chiharu stands alone, embraced by a phantom partner.

The volume begins with short vignettes of a young housewife, mother of two daughters, doing what some might call women’s work: tidying up after the children, preparing a late dinner for her husband, playing with her children, shopping, dealing with the neighbors’ demands, and desperately trying to get her husband to help with the household. She loves her daughters, but at the same time, she is annoyed by how much they demand of her. Worse, the older they get, the less they need her, leading to a lonely emptiness.

Her husband is also often absent, claiming to always be at work, although the matchboxes from love hotels suggest otherwise. When he is at home, he treats her like a maid, even calling her from another room to change the channel for him instead of getting up.

She rebels, and her husband grows more distant from her. She takes a part-time job, discovers doll-making, and begins a life in which she is almost happy. The humor is subtle, the melancholy overwhelming. Chiharu is hungry for life, for fun, for joy: she loves to run barefoot through the rain, she has skills and talents, and she doesn’t want to become invisible to please others. The stories in “Talk to My Back” are stories about a woman trapped in a life that brings her no respect but imposes great responsibility: she tries not to hurt her children; she tries not to be hurt by her husband; she tries to remain herself and not the embodiment of the bad mother, the nagging wife. She doesn’t always succeed. But she tries.

If there is one word to describe Murasaki’s illustrations, it would be “minimalistic.” Delicate, flowing lines run across the pages, giving a certain grace to otherwise sober characters. This allows her to capture impressive and powerful moments, whether it is the empty space in a hallway where a lonely woman misses her husband, or the same woman watching clouds in a puddle with her children.

The book is accompanied by an essay by translator Ryan Holmberg, which places Murasaki’s role in the field of classic manga in the proper context and shows why she was often ahead of her time—not only through her choice of subject matter but also through the subtle way in which she addressed issues related to the feminist debates of her time. Chiharu’s burgeoning financial independence and her creative hobby reflect Murasaki’s own life, as we learn in Holmberg’s essay. After her marriage, Murasaki stopped drawing comics, but eventually, she secretly started again. She feared her husband would kill her, but to leave him, she needed money, and she knew she could earn money with comics. She called editors from public phones, “smuggled” her works out of the house, and met with editors in cafés. In 1981, she finally managed to separate from her husband.

Reading this book is essential if you want to understand the background of this manga or learn more about the artist behind it.

Drawn & Quarterly publishes “Talk to My Back” in a large format. The quality of the paper is noteworthy. Other details also show that the publisher put a lot of effort into it. There are some colored pages and a colored inner cover.

Is it worth reading?

“Talk to My Back” is a complex but captivating collection of emotions and everyday domestic struggles. However, in my opinion, the manga is more accessible than it might seem at first glance, and even if you are not very familiar with Garo works, you will quickly get into this manga.

If you are looking for an intense manga that deals with the role of women in Japanese society, this is definitely the right place.

Talk To My Back GN TP by Murasaki Yamada

€29,95

Set in an apartment complex on the outskirts of Tokyo, Murasaki Yamada's Talk to My Back (1981-84) explores the fraying of Japan's suburban middle-class dreams through a woman's relationship with her two daughters as they mature and assert their independence,… read more

.png)